| Music Typesetting on Linux: An Interview with Mike Mack Smith | |||

| By Chris Cannam | |||

If you read sheet music, you may have wondered how it's produced. Are there armies of people frantically pointing-and-clicking with Windows score-editing packages? Do they rush out and buy the latest version of Finale whenever an upgrade comes out? You can imagine how to print hundreds of thousands of copies of the latest Harry Potter: it's all plain text, and it's easy to see that you could use some standard software to typeset it. But for a complex score, with less money behind it, in a smaller print run? The answer, surprisingly, may involve Linux. Here Linux Musician presents an interview with Mike Mack Smith, co-founder of Barnes Music Engraving, one of the UK's most well-established and respected computer-based music typesetting companies. Interview by Chris Cannam.

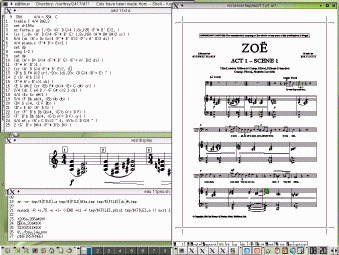

Chris: So first, why "music engraving"? Mike: It's an historical thing, dating from the time that music was engraved into pewter plates, in mirror image. We use the term loosely. We justify it by the fact that the image is "engraved" onto photographic paper by a laser, but music typesetting might be a better term. What form do you receive the music in? Usually we receive a manuscript from the publisher, maybe hand written, or a previously set work with alterations, or set by another computer based system. Or for some publishers we also act as arrangers: they supply us with a CD and ask us to make an arrangement, say, for piano and vocal with guitar chord boxes. And what form do you turn it into? Until about four years ago, we used to supply the final image from a high resolution imagesetter, usually around 3,000 dpi. Now, all finals are supplied as PDF files. PDF seems to be a pretty good standard. We used to have awful problems when we supplied stuff in EPS form. There were often many problems sending files to printers, especially if they were Mac based -- usually to do with embedded fonts. So far there have been no problems with PDF, and they are so compact that delivery via e-mail works very well. Can you give a quick description of the software and hardware setup you use? A basic Linux installation. We've used SuSE for the last couple of years. The music typesetting system is called Amadeus, developed by Wolfgang Hamann and Kurt Maas and first released about 17 years ago, running on PDP11/73 with the Idris operating system, which was a Unix lookalike. Input was on terminal monitors. You didn't see the music until it came out of the imagesetter. Strangely, this was very good training for everyone! Around 1990, we started using Atari STs, and we could actually see the music on screen. And in about 1994 started using Linux. Wow! The software is really a music formatting system. You give the basic music information for each stave, with no concept of layout. Then when you have all the parts, you give some dimensions and ... you have proper music! It's very un-point and click. We can now enter whole lines of music without looking at the screen once, just at the manuscript -- although in practice we do check what we are typing. It's basically copy typing for music. It combines well with text formatting -- a version of troff -- and with programs for incorporating TIFF images etc, and of course it also generates midi files. Wolfgang Hamann has had to do some re-writes on software, and we still have perennial problems that the software still uses some very old libraries which SuSE stopped shipping after 7.0. The reason we stick with it, rather than something like Finale or Sibelius, is that we can customize it to do whatever we want, not what a programmer has determined in advance that we want! It sounds a bit like Lilypond. Have you ever considered trying to switch to a free-software alternative like that? Any idea what the pros and cons might be? Well, we believe that Amadeus produces the best quality in the most efficient way. Music publishers can be very picky about the smallest aspect of music setting... and so are we. Certain music setting packages may be great as composing and arranging tools, but do have deficiencies when it comes to the presentation of the music for print. I haven't had a long look at Lilypond, but my guess is that Amadeus is more advanced. It can, pretty much, deal with anything, so long as it's conventional notation (and some deviations). The cost of any software or equipment doesn't figure highly: we'll buy anything that enables us to produce our product more efficiently. When you're doing it eight hours a day, any improvement in efficiency will soon pay off. And the rest of your setup? System wise, on site we have a server and backup server, about five Linux workstations and three Windows workstations, and printers for supplying proofs and check proofs. We need the Windows stations for company financial software. We can't find appropriate stuff in Linux -- Sage e-mailed that they had no plans for a Linux port. We also tend to use Photoshop, although I'm trying to force myself to use Gimp. The most important use for Windows is to run Acrobat Distiller, which seems to always produce a bomb proof result. We have had problems with the Postscript to PDF converters within Linux. Sometimes we also need to use page makeup programs such as Quark or Adobe InDesign to combine graphics, music and text. Sometimes it's so complex you need to see on screen what's happening, and be able to change it. Do you have a typical sort of client with a typical style of music? We'll work for anyone! ... Actually we won't. We tend to work for established publishers. Working for private individuals never seems to work well. We work for publishers such as Oxford University Press, ABRSM Publishing -- the people that do all those exams --, Novello, Boosey & Hawkes. Types of work are hymn books, full orchestral scores, choral leaflets and anthologies, educational books with text and music, exam papers, piano, vocal and guitar box arrangements of pop songs, easy keyboard arrangements, etc. And are any of these particularly difficult to deal with? Each of them provide their own particular problems. Full scores are probably the trickiest, and least profitable. Hymn books are usually a case of organization: there can be over eight hundred items, which have to be set in a coherent and consistent style. Educational books can be a bit of a pain as we have to use Windows for page makeup programs, Adobe InDesign or Quark Xpress. Composers sometimes start inventing their own non-standard system of notation. This is not good news for anyone! We will usually drop these projects as soon as possible! So how much involvement does the client get in deciding how something will look, and how much control do you get? It very much depends on the customer. In some cases the customer leaves everything up to us; this is sometimes a good thing and sometimes a bad thing! When it's done by the customer knowing that we are able to take what they have given us and create a good product, it's good. When it's done out of ignorance by the customer, it can be bad! We will usually send samples back to the client before we set the whole job, for them to okay, and any alterations to style from that point would be chargeable. How much work goes into typesetting a single piece? Pages can take anything from ten minutes to half a day to set. It depends on the complexity of the music, but also of the music typesetting software's ability to deal with it. We usually spend quite a lot of time setting up a job -- centralizing data as much as possible, making shortcuts, etc. A good setup greatly reduces the amount of time an individual page takes to set. For a hymn book, we may take a week or two just doing the setup. This always pays off. Don't you get sick of seeing and hearing the same thing over and over again? Surprisingly, all pieces are different, providing their own problems. Sometimes it does get a bit like a production line, but then we just try to get it done as efficiently as possible -- "what the heck, where's the cheque!". This tends to be quite an incentive! Listening is only a small part of what we do. After the piece has been set, we will give it a quick MIDI proof, just to check that there aren't any major blunders like wrong key signatures. The most important proof is the side-by-side visual proof, comparing the proof against the original manuscript. Whilst we're setting the music it is very much a visual thing: we don't consider how it sounds, only how we can lay it out to help the performing musician as much as possible. After having worked on a piece of music for a few hours, it's usually quite interesting to hear what it sounds like -- and if it was worth it! Is this the sort of business you can imagine readers of this article being able to get into, if they wanted to? How would someone interested in this set about finding work doing this sort of thing? It's an overcrowded pool already. Ten years ago, life was much easier. Then along came these packages that you could buy for five hundred quid, as opposed to ten grand for Amadeus, and everyone who couldn't get a job after leaving music college went into competition with us. We did warn publishers that there was more to it than just having a bit of kit -- but back then, music publishers were run by accountants, and it took a few years for the penny to drop. After getting stung quite a few times, publishers have learnt: single operators are used, but only when they have a proven track record and have a body of work to show. Prices have tended to remain static for the last ten years. The only way we can survive is to constantly get more efficient. Finally: the name of the company is Barnes Music Engraving Ltd, but who or what is or was Barnes?

When setting up the company sixteen years ago we needed a name. We were trying to think of something that gave the impression of stability, avoiding the fly-by-night impression of "Lasermusic", or "Cadmus" or "Jet Set Music". After going through various local Sussex connections such as "Dowlands" or "Woolfs" we ended up going through a list of people we were at school with. After discounting "Nibble" and "Oraface", my collegue suggested "Barnes", which I thought had the right tone. We even invented a founder of our company called "Malcolm Earnest Barnes", who still has an account on the Linux system! Oh well, it seemed funny at the time! |

|||